Interior Automotive Designer

We love our cars – and not just how they look on the outside. The interior design of today’s automobiles is every bit as important to the American consumer as the exterior styling. We are drawn to convenient features, gorgeous colors, luxury upholstery fabrics, ergonomic seats, and technical wizardry. Surprisingly, the interior of today’s cars reflects the mid-20th century influence of a remarkable female designer: Helene Rother, the first woman to work as an automotive designer.

Educated at a prestigious school of art and the Bauhaus in Germany, Rother began her career in visual arts and graphic design. In Paris, she designed popular miniature animal pins worn by women on hats and dressed before WWII. In 1941, she fled Nazi-occupied France with her seven-year-old daughter to a refugee camp in Casablanca before finding passage to New York City, where she started her fledgling American design career as an illustrator for Marvel Comics, a largely unsuccessful book author and illustrator, and a textile designer in the minimalist style of Le Corbusier and Bauhaus.

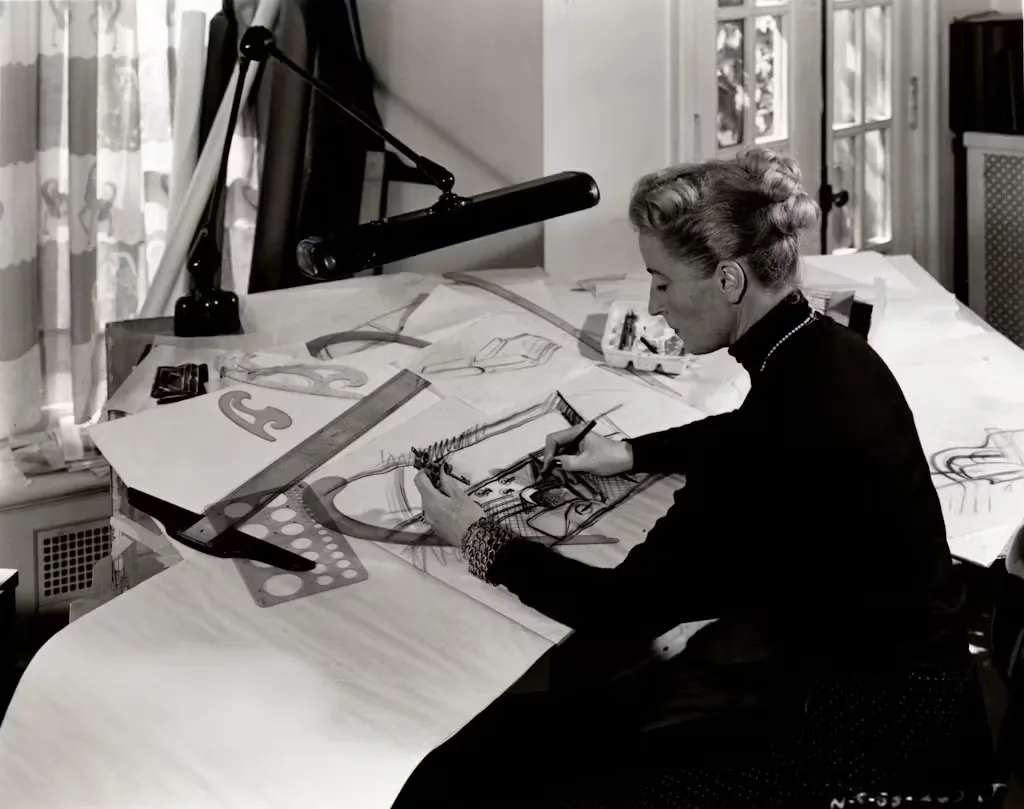

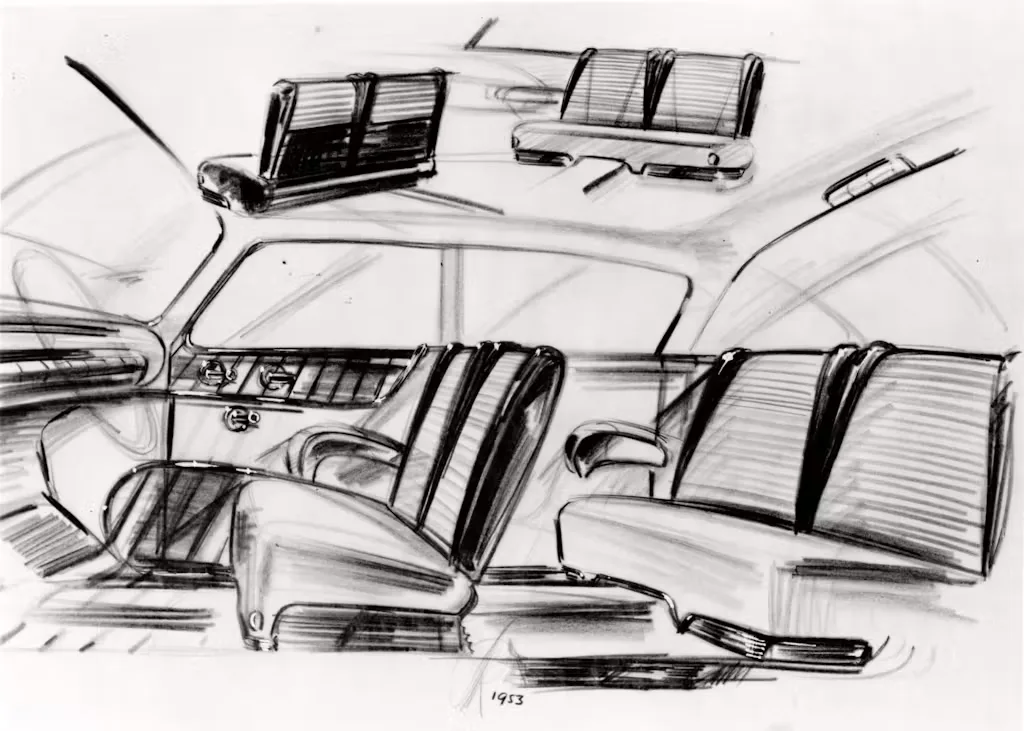

In 1943, Rother –a single mother whose husband had been active in the French Resistance– was invited to join the interior styling staff of General Motors in Detroit, becoming the first hire of a group of GM’s “Damsels of Design,” whose members incorporated intuitive innovations such as tissue dispensers, flashy finishes, and textured fabrics in a kaleidoscope of colors. “I have a long list of gadgets for use in cars beginning with outlets for heating baby bottles and canned soup, cigarette lights on springs, umbrella holders and so on,” Rother once wrote. In 1944, she made preliminary sketches for both seating configurations and wall coverings for a GM passenger train concept called the Train of Tomorrow.

According to writer Patrick Foster, Rother was “one of the few women to succeed in a man’s job during an era when the vast majority of women couldn’t even see a glass ceiling – it was hidden behind steel doors.”

In 1947, Rother established her own design studio specializing in automobile interiors, furniture, and stained glass windows. Her 1948 article, “Are we doing a good job in our car interiors?” was published by the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE). “The instrument board of a car,” she wrote, “shows above anything else how well-styled the car is. Here the driver is in real contact with the mechanics, and here is the greatest test of good coordination between the engineer and the stylist.” In 1948, Rother became the first female presenter at SAE’s annual conference.

But it was her work on the Nash Rambler – that innovative, saucy, and once-coveted mid-century compact marvel – that solidified Rother’s reputation at the top of her class. Rambler featured seats, moldings, garnish, trim pieces, and fabrics designed by “Madame Helene Rother of Paris.” The revolutionary Airflyte models showcased her refined artistic design elements using color, fabrics, and texture throughout. The company focused on the lifestyle of its targeted customers – women – leaning on Rother’s belief that women of the time liked gadgets. Images of women driving the car filled the pages of glossy magazines of the era. Redesigned in 1953 and temporarily lifted through a merger with

Hudson in 1954 (later American Motors), the short-lived Rambler is acknowledged as the first successful modern American compact car.

After leaving Nash, Rother worked with Goodyear Tire, BF Goodrich, Magnavox, and International Harvester. She designed the interiors of ambulances and hearses, as well as a flatware pattern called “Skylark” for Samuel Kirk & Son. In the mid-1960s, she oversaw many stained-glass installations for churches, especially in Michigan, where some of her glass still graces cathedrals in the Detroit area. (Sadly, her name is little known in the world of stained glass.) Later in life, she dedicated herself to her own work and her horses. Rother died in 1999, nearly 22 years before being inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame.

Accolades and Honors

- 1948: First woman to speak at annual meeting of Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE)

- 1949: SAE Journal praises her efforts in jewelry, accessories and automobile design

- 1953: Awarded the Jackson Medal for excellent of design, one of America’s most sought-after awards

- 1953: Tide magazine writes, “an industrial designer with an impressive record”

- 2020: Inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame