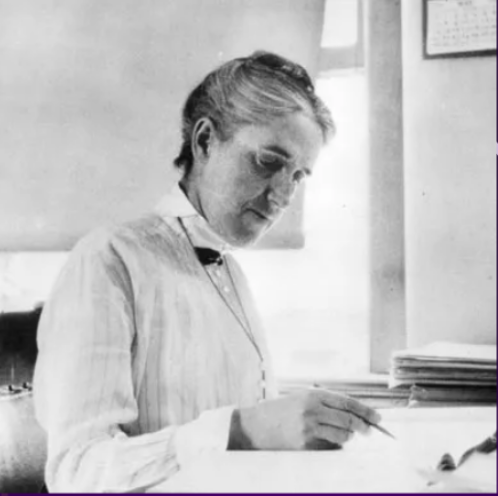

She looked to the stars and made a great discovery

How far is it from one galaxy to another? The discovery of how to effectively measure vast distances to remote galaxies is the legacy of a great American female astronomer, Henrietta Swan Leavitt. Her work led to a monumental shift in our understanding of the scale and nature of the universe. Leavitt first came to the Harvard College Observatory as a student at Radcliffe College, toiling there as a human computer, measuring photographic plates to catalog the positions and brightness of the stars; women were not allowed to operate the telescopes themselves. Through her work, she earned credits for a graduate degree in astronomy that she could not complete due to illness. Leavitt became a staff member in 1898, leaving to make two trips to Europe and serving as an art assistant at Beloit College in Wisconsin, where she contracted an illness that led to progressive hearing loss.

She returned to Harvard in 1903 but was initially not paid because she was financially independent; later she received 30 cents an hour for her work. (Imagine either scenario today.) Leavitt’s innovative thinking provided astronomers with the first standard “candle” with which to measure the distance to other galaxies. Prior to her discovery of the period-luminosity relationship for Cepheid variables (referred to as Leavitt’s Law), the only techniques available to astronomers for measuring the distance to a star were based on stellar parallax, which can only be used for measuring distances out to several hundred light years. Her discovery became a measuring stick with vastly greater reach.

This excerpt from Wikipedia sums up her profound impact on astronomy: “After Leavitt’s death, Edwin Hubble found Cepheids in several nebulae, including the Andromeda Nebula, and, using Leavitt’s Law, calculated that their distance was far too great to be part of the Milky Way and were separate galaxies in their own right. This settled astronomy’s Great Debate over the size of the universe. Hubble later used Leavitt’s Law, together with galactic redshifts, to establish that the universe is expanding.” Hubble’s Law was only made possible by the groundbreaking work of Henrietta Swan Leavitt, a deaf astronomer with a humble attitude and an impeccable work ethic.

In 1921, Leavitt was made head of stellar photometry at Harvard, but by the end of that year she had died from stomach cancer. Hubble always said she deserved the Noble Prize, and a posthumous attempt to nominate her was, predictably, not successful. In modern times, her legacy has been captured in popular literature, biographies, children’s books, staged plays and a BBC television series.

Awards and Accolades

Memberships: Phi Beta Kappa, the American Association of University Women, the American Astronomical and Astrophysical Society, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and an honorary member of the American Association of Variable Star Observers.

Posthumous Honors:

- The asteroid and the crater Leavitt on the Moon are named after her to honor deaf men and women who have worked as astronomers.

- One of the ASAS-SN telescopes, located in the McDonald Observatory in Texas, is named in her honor.